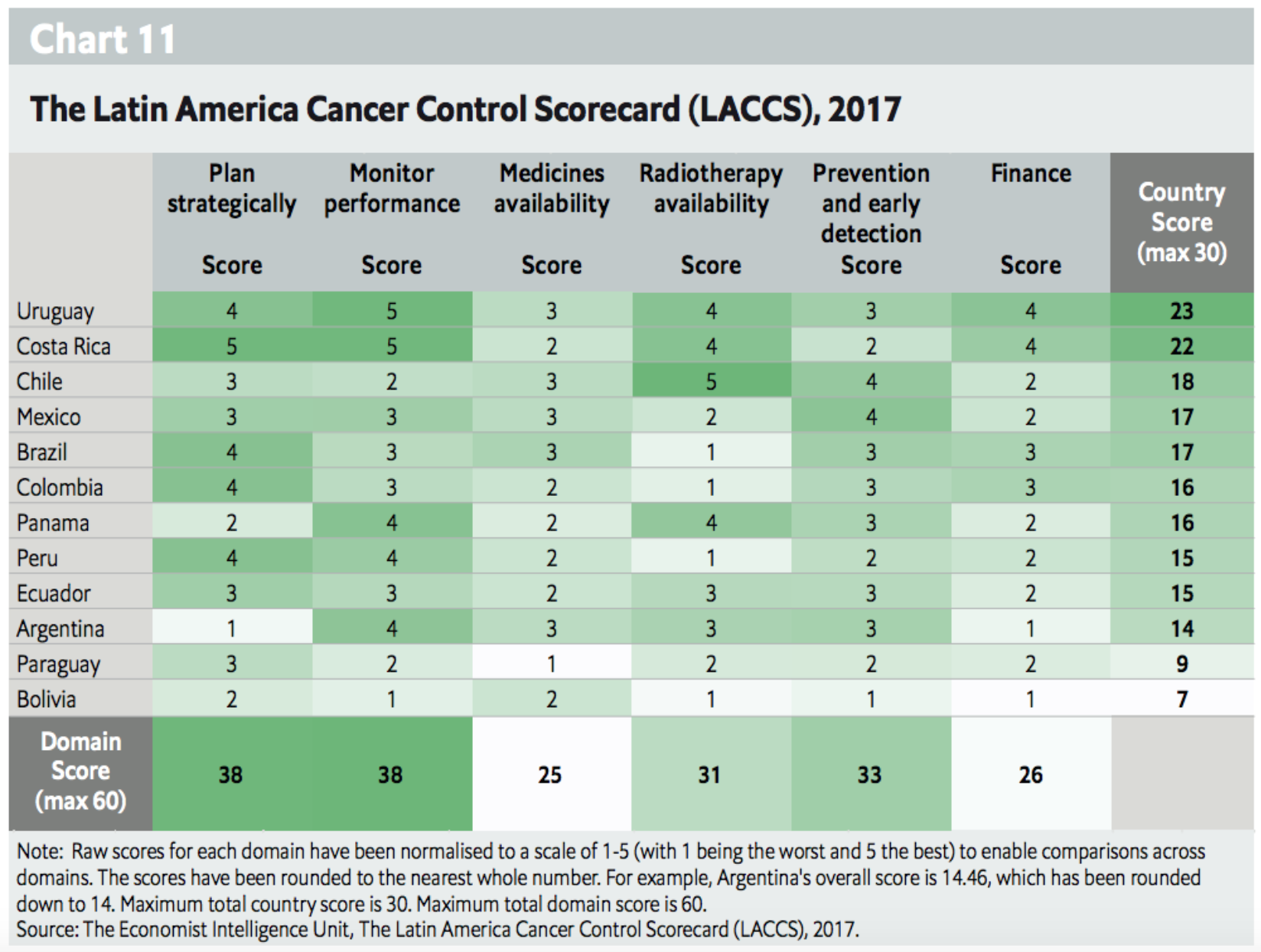

In a recent report by The Economist, commissioned by multinational healthcare company Roche, Peru was ranked eighth among 12 major countries in Central and South America in regard to the country’s cancer control efforts.

According to the report, cancer is the second leading cause of death in Latin America and is expected to worsen over the coming years. The report details that in Peru the percentage of all deaths attributable to cancer increased from 10% in 1990 to 19% in 2015. The dismal outlook of cancer within Latin America piqued the interest of researchers in the study.

To determine the rankings, each country was scored on a scale of one to five on six key areas, including strategic planning; performance monitoring; medicine availability; radiotherapy availability; prevention and early detection; and financing. The scores for each category were then summed together. Peru scored 15 points out of 30, coming in at 8th place.

Screenshot taken from report “Cancer Control, Access and Inequality in Latin America” by The Economist

As the chart shows, the low ranking assigned to Peru does not provide the full story of its current state. In fact, the report asserts, “Peru and Colombia, in particular, do far better than would be expected given the size of their economies, largely because of detailed cancer control plans.”

In terms of strategic planning, Peru ranked very high due to the government’s Plan Esperanza, launched in 2012 as part of its National Plan for the Urgent Attention of Cancer and the Improvement of Access to Oncology Services in Peru.

The aim of this plan was to improve both the quality and access of available cancer prevention and treatment services by expanding federal funding within the public health system, which jumped from 2.3% in 2011 to 6% by 2015. Plan Esperanza has, in fact, been frequently cited as a model for other countries to develop similar National Cancer Control Plans (NCCPs).

Additionally, it is worth noting that despite the fact that the GDP per capita of Panama and Argentina is roughly double that of Peru, the three countries earned a nearly equal score in the report. A striking difference is that both Panama and Argentina scored higher in terms of treatment availability.

How can Peru improve?

Treatment availability and finances are ultimately the two areas that Peru needs to turn its attention to, in order to improve its cancer management services.

In fact, according to a post by El Comercio, without counting the government’s social security health program and the private sector, there are only two Ministry of Health (MINSA) centers that offer radiation treatment: the National Institute of Neoplasic Diseases (INEN) in Lima, and the Goyeneche Hospital in Arequipa.

This highlights a large problem currently faced by the country, which is further explained in The Economist report by Dr. Carlos Vallejos, Director of Oncosalud in Peru: “Peru is too big [for care concentrated in cities to work]. We don’t have good roads. From the jungle, the only way to reach Lima is by airplane—and that is expensive. It would be impractical for everyone to go to a cancer institute. We have to look for the rural population and provide them with services.”

In order to overcome this glaring obstacle, the country will need to wisely invest a larger proportion of funds in the areas that currently lack access to cancer detection and treatment facilities. Moreover, the country will need to focus on the decentralization of cancer care to expand treatment beyond Lima, the country’s capital—a process that has already been underway.

Finally, the study concludes that Peru can improve its distributed care by leveraging its existing network of community health workers for a variety of services from vaccinations to basic diagnoses.

The report indicates that achieving these targets is increasingly important for the Latin American cancer outlook: cancer incidence will likely rise across the region, and without intervention, mortality rates could more than double by 2035.