Lima, Peru — The meteorological phenomenon known as Coastal El Niño is a recurring climatic event that has caused significant floods and landslides in the coastal region of Peru and other South American countries over the years.

Now, researchers are warning that Peru may be bracing for a particularly strong Coastal El Niño phenomenon this summer, which could bring heavy rains to the northern part of the country.

According to the latest report from the Multisectoral Commission responsible for the National Study of the El Niño Phenomenon (Enfen), the probability of this phenomenon manifesting strongly in the summer of 2024, which begins in January, has increased to 49%. The probability of it manifesting in a “moderate” way has decreased to 47%.

These estimates represent a significant increase, as in the previous communication issued on October 13, the probability of Coastal El Niño manifesting with “strong” magnitude was 33%, and “moderate” was 55%.

“Coastal El Niño is expected to continue at least until the beginning of the autumn in 2024, as a result of the evolution of El Niño in the central Pacific. It is more likely that strong warm conditions will persist until February,” read the statement.

Coastal El Niño is a variant of the El Niño phenomenon, characterized by an abnormal warming of the surface waters in the equatorial Pacific Ocean.

While El Niño events are often associated with heavy rains and landslides in the Andean region, Coastal El Niño specifically focuses on the devastating effects that occur along the Peruvian coast, primarily in the regions of Tumbes, Piura, Lambayeque, La Libertad, and the capital, Lima.

This phenomenon is notorious for its ability to trigger floods and landslides in highly populated and vulnerable areas.

Grinia Ávalos, the Deputy Director of Climate Prediction at the National Meteorology and Hydrology Service (Senamhi), told Peru Reports that “a scenario ranging from moderate to strong for the upcoming summer could mean that rainfall levels above normal may occur.”

“We do not rule out heavy, strong rains in the northern part of the country. And the Senamhi forecast indicates that it is more likely to see scenarios with above-normal rainfall for the summer,” she stated.

According to Ávalos, Peru is “entering the period of the highest temperatures of the year, and under these conditions, in an El Niño scenario, we cannot rule out the possibility of an event like the one in March, with Cyclone Yaku.”

The cyclone destroyed more than 6,000 homes, and left a total of 84 people dead, according to a report published by the National Institute of Civil Defense (Indeci) in April.

In addition, the floods triggered an unprecedented dengue epidemic in Peru, reaching the highest per capita dengue rate in the Americas, with a historical record of over 172,000 dengue cases and 287 deaths, according to United Nations data. Due to the high number of dengue cases, on May 10, the Ministry of Health declared a health emergency in 20 out of the country’s 25 regions.

Ávalos explained that in order to be certain that a new cyclone could strike Peru again, it is necessary to “closely monitor the atmosphere, the winds, and how the pressures change to make that forecast.”

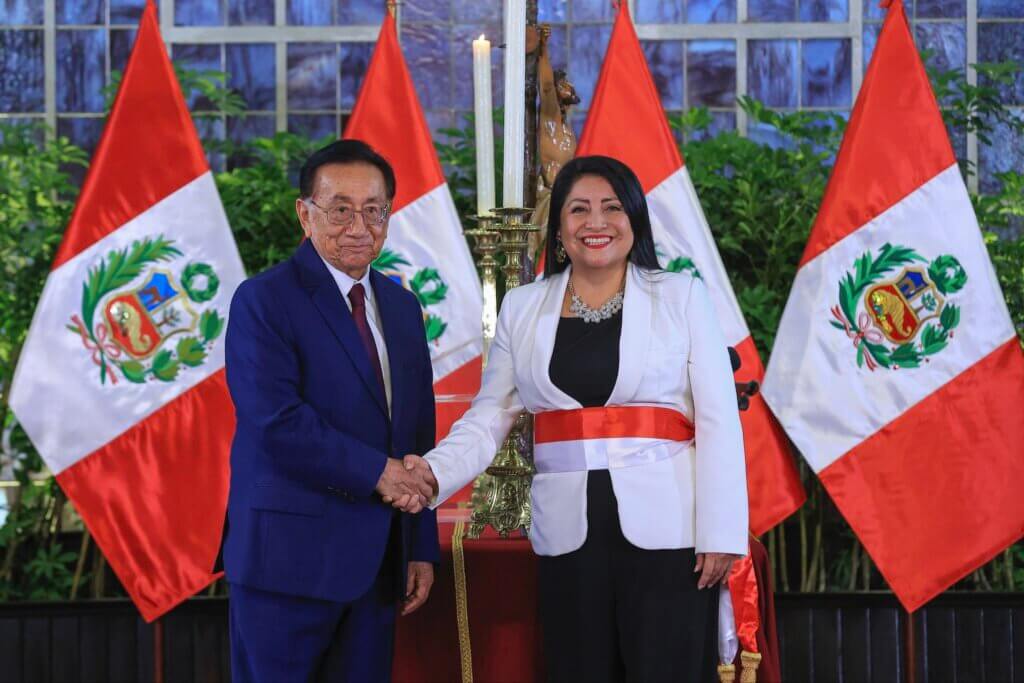

After it was revealed that the likelihood of Coastal El Niño striking forcefully in 2024 had increased, Prime Minister Alberto Otárola allocated a special budget for damage prevention initiatives.

“Several ministries have been working on this quietly but efficiently over the past few months,” he told the media.

He also explained that there are projects that Dina Boluarte’s administration cannot carry out and placed the blame on the management of previous governments.

“We couldn’t undertake major prevention projects because previous governments simply didn’t do them. So, what we have done is the river cleaning work” where solid waste has been accumulating, he added.