When various players in the Peruvian startup ecosystem are asked why a unicorn has not yet been born in Peru, the answer is almost unanimous: “We have entered this late.”

Both the question and the answer are timely when one appreciates the speed and growth shown by its neighbors Chile and Colombia, not to mention Brazil, Argentina and Mexico. However, it is precisely the evolution of these ecosystems and their turning points that make us see that Peru’s time has finally come.

Latin America in a wave diagram

Latin American startup ecosystems have followed similar routes of progress over the last fifteen years, according to Greg Mitchell, managing director of AVP, a Mexican VC fund with a presence in several countries in the region.

In this period of time, three waves of development have been observed in the ecosystems of Mexico, Colombia, Chile and Peru. With the exception of the Peruvian case, the rest have already gone through them. The first wave is one of governmental support in economic, promotional and convening issues. The second, when the venture capital industry focuses on local startups, which offer their first success stories by raising rounds of international investors. The third wave is the inflection and consolidation point: when startups become regional with valuations of more than $100 million.

Successive waves in Mexico, Colombia and Chile have already given birth to unicorns such as Kavak, Clip, Rappi, Platzi, NotCo and Betterfly. For Mitchell, the Peruvian ecosystem is entering the third wave, which means two things: that, on the one hand, there are now serial founders and solid teams; and, on the other hand, a local venture capital industry with several active funds such as AVP, Inca Ventures, Salkantay or Winnipeg, as well as accelerators such as UTEC Ventures. As of today, the Peruvian Association of Seed Capital and Entrepreneurship (PECAP) has 50 active members.

The conditions are in place, according to Mitchell, but despite the activity and dynamism that the Peruvian startup ecosystem is showing, it is not attracting the same levels of money as its neighbors. “That represents an opportunity for investors. The necessary inputs exist for the third wave to be successful. What is lacking is capital, both local and foreign, to give the necessary boost to these startups. The plane is ready to take off, it’s just a matter of putting the gas in,” adds Mitchell.

The importance of a unicorn

The Rappi phenomenon in Colombia is now an experience to be replicated in the Peruvian ecosystem. It has shown the importance of achieving unicorn status to generate a chain reaction and a virtuous circle. For Gonzalo Begazo, CEO of Chazki, a last-mile logistics startup, tipped to be one of the first Peruvian unicorns, the Rappi effect in Colombia has led more and more Colombians to enter Y Combinator and similar programs.

José Deustua, director of UTEC Ventures, comments that one of the most important consequences of a phenomenon like Rappi is the large increase in investments in the sector. “But what we need more than unicorns is to look for more exits. That is what allows us to grow at a good rate,” he adds, and predicts that in three years at the latest there will be one or more unicorns made in Peru.

Along with Chazki, Crehana, an edtech with presence in Peru, Colombia and Mexico (and entering Brazil), which in August 2021 raised a $70 million series B led by General Atlantic, is also mentioned as a candidate. Another one in the spotlight is Favo, a social commerce platform that in October 2021 raised $26 million in a round led by Tiger Global to expand in Mexico and Brazil. Other Peruvian startups that have completed successful rounds in recent times are Turbodega ($3 million in November 2021), Crack the Code ($2.7 million in December 2021, led by Kaszek) and Leasy (which raised $17 million in February 2022).

For Luis Narro, venture partner at Alaya Capital, a regional VC fund, it is a matter of time before the first Peruvian unicorn is born.

Mitchell is even more optimistic. “I believe that the first Peruvian unicorn has already been born or is about to be born in the next few months,” he states flatly. “But it’s not enough to have just one. The goal we seek is to create a dynamic ecosystem that fosters many successful startups, with access to various funding avenues, both local and foreign. We need to invest more money in more startups. It’s a numbers game. We cannot achieve what other countries are achieving if we invest so little money in so few startups. We have to invest in and support many startups to create a dynamic place where the cost of startups can be reduced.”

The moment of take-off is now

When looking at the growth curves of the different Latin American ecosystems, it can be seen that there is a “take-off moment” that serves as a turning point in the third wave.

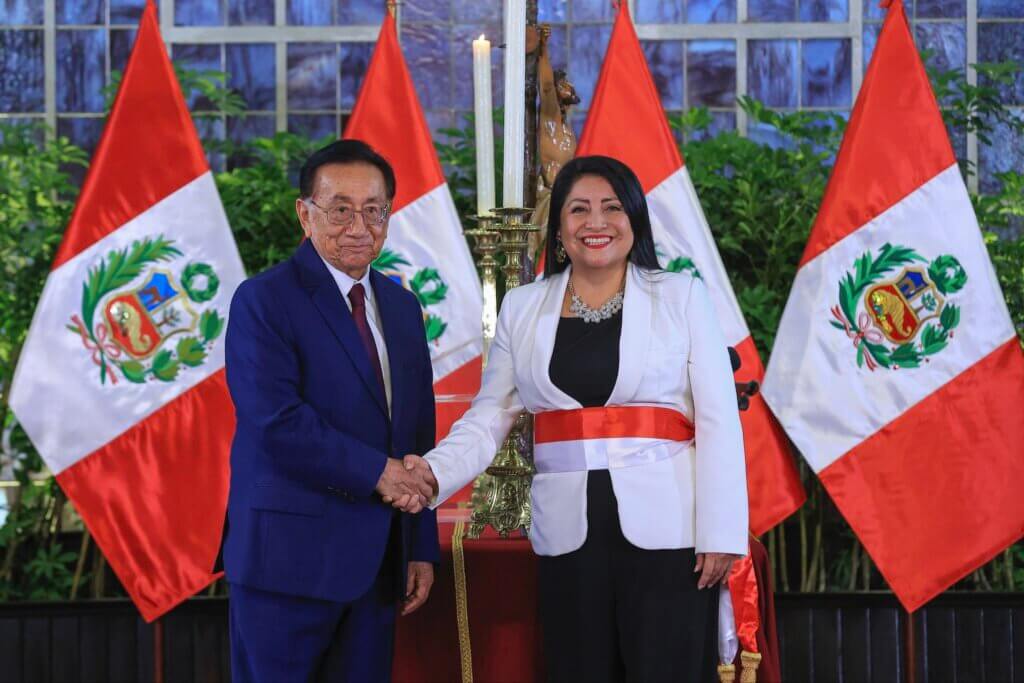

Greg Mitchell, Managing Director of AVP (left), with the former First Lady of Peru Nancy Lange. Image courtesy of @gregenperu via Twitter.

This occurs when venture capital investments exceed $10 million per year and, in addition, when funds of funds are created by the State. According to Mitchell’s analysis, when these two characteristics appear, the “moment of take-off” has arrived. And these two are fulfilled in the Peruvian case.

Over time, it has been observed that countries reach this great moment more and more quickly and, from then on, their growth is faster. Mitchell notes that it took Colombia less time to go from $10 million to $200 million than it took Mexico (which had taken off a few years earlier). This would mean that in the case of the Peruvian ecosystem, growth can be accelerated.

Peru has not needed a unicorn for its ventures to be present in Y Combinator, 500 Startups, Parallel 18 or Techstars. This reinforces the idea that the moment of takeoff of its ecosystem has already begun. The question now is: What is the name of the next Peruvian unicorn? The answer remains to be seen in the coming months.