“She was sterilised, and then thrown in the morgue, left for dead,” Rosemarie Lerner said. “She woke up hours later surrounded by corpses and had to scream for anybody to hear her and get her out. She’d been left there, like rubbish.”

This is one of the stories from the Quipu project, which was created by Lerner and Maria Court to allow thousands of women who were sterilised by force to tell their stories. These sterilisations were part of a ‘Family Planning’ programme implemented by President Alberto Fujimori between 1990 and 2000, but many of the sterilisations were far from consensual, and nearly 300,000 women were medicated against their will, their now-barren bodies used as objects to fulfil government-set targets.

Peru Reports interviewed Lerner, who told tales of how women were tricked into undergoing a surgery they didn’t understand, how some husbands stepped up to protect their wives, and how Peru’s divided society allowed this to happen without it ever reaching the headlines.

One of Lerner’s friends had a mother who is famous among Peruvian activists; Giulia Tamayo, a lawyer and feminist who worked tirelessly to create legislations that would protect human rights. She was the first person to investigate the case of the forced sterilisations whilst it was taking place in the 90s and created campaigns and protests to mobilise people and raise awareness of Fujimori’s wrongdoings. In return, Tamayo received death threats from the Fujimori regime itself, and her implacability and refusal to let go of the case meant that she had to flee to Spain in order to maintain her and her family’s safety. Tamayo spoke to Lerner about the regime before her death in 2015, and Lerner remembers the quote to this day.

“They very arrogantly thought that because they were indigenous, they were poor women, they wouldn’t speak,” Lerner remembers Tamayo saying. “But they were wrong because they spoke.”

Interest well and truly peaked, Lerner and co-creator Maria Court decided to create a non-linear documentary that would allow the women to tell their stories without feeling as if they were being exploited by a media they didn’t trust. Many women had already told their stories to foreign media sources who then disappeared and published their stories without giving anything back to the women, not even a photo.

“[The women] were tired of that and that was one of the reasons we thought of something participatory, something interactive, or something that we can leave behind for them and they can create for them to use,” Lerner explained. “It’s more creating a platform or a set of tools for them to tell their stories in their own words.”

The Quipu Project was born from these stories, while also allowing women to partake in workshops and tell their own tales with phones gifted to them so that they could be finally be heard. The project, named after an ancient Quechuan communication method using strings and knots, then amassed all these recordings onto an online platform where anybody can listen to the narratives and can even record a response.

https://t.co/FMdOERB5uX

El #ProyectoQuipu nace para que las voces de personas afectadas por las #EsterilizacionesForzadas sean escuchadas y nunca olvidadas apoyando la lucha por justicia y contra la impunidad. #NoAlIndulto #EsterilizacioneaForzadas. #EscuchaYcomparte pic.twitter.com/82Ba7fxBYR— Quipu Project (@QuipuProject) 26 de enero de 2018

Some of the stories are harrowing. Lerner explained that the Fujimori regime gave doctors and medical centres quotas of the number of women to be sterilised, and that they would win prizes if they reached them, or risk losing their jobs if they didn’t. This was also reported by CLADEM, a group of women’s NGO’s based in Latin America and the Caribbean (pages 41-43), as well as in a 1998 hearing on the “Peruvian Population Control Campaign” before the Subcommittee on International Operations and Human Rights in the US, where a researcher affirmed that quotas, or goals, had been set by the government.

“Health officials, doctors and other health workers would generally feel an obligation to meet these goals and would fear that their contracts would be removed if they failed to meet these goals,” one of the conclusions read. “Other abuses, such as lack of informed consent, pressure to consent, bonuses per woman sterilised and trading food for consent were probably not mandated by the central government but were the natural outcome of the mandate that the goals must be met.”

“How can you have a quota of something that is supposed to be voluntary?” Lerner asked. “And people didn’t understand the procedure because it was so new – it had only been created a couple years before.”

In the workshops they led with the women, many compared their scars. Some scars were small, some big, some horizontal, some vertical. It was clear that the doctors who were carrying out the operations were inexperienced or incompetent and were just trying to fulfil their macabre quotas.

It’s not the lack of medical skill, but the lack of consent that still motivates activists like Lerner to tell these brutal stories. Lerner explained that the medical workers used a variety of dirty tactics to coerce the women into having the procedure.

“One common [story] was that they came and told them they had to have the surgery because if they had more children they would have to pay a fine or go to prison,” she explained. “Or there was a tax per child, or that their child wouldn’t be registered at the health centre and they wouldn’t attend to them or their child.”

Lerner added that women were often tricked and promised food in exchange for the supposed treatment. Pregnant women were opened up with C-sections and covertly sterilised while under anaesthetic.

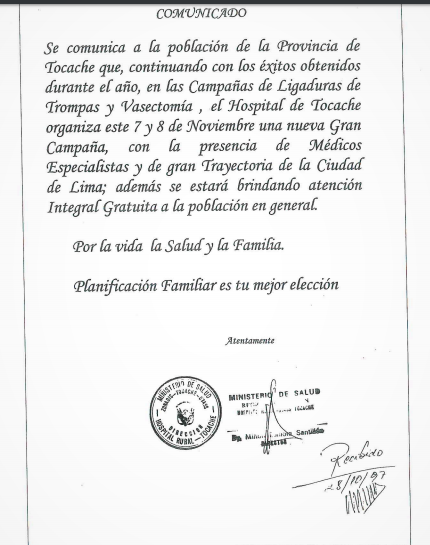

One of the campaign posters for sterilisations.

“For life, for health, for family, Family Planning is your best choice.” Photo courtesy of CLADEM study.

Officials were not shy about forcing the practice on women, either. She detailed how authorities would knock on doors, sometimes capturing and locking up women who were reluctant. “They were literally held down,” she said.

Posters were distributed encouraging women and men to attend Family Planning campaigns, where they were offered free health checks in exchange for attendance.

“Other cases, they said ‘Yes,’” Lerner continued. “But they didn’t know what it implied, or what it meant, even if they consented and said they didn’t want any more children, the surgeries took place in bad conditions, because they were trying to do so many, so quickly.”

Sometimes the women were taken miles from their villages to the health centre where they underwent the procedure, before being dumped outside immediately after and forced to walk home.

It is not just women who were sterilised. Out of the 300,000 or more people who were sterilised by the programme, around 20,000 were men, although the number could be higher due to a lack of men admitting to having gone through the procedure. In some cases the men refused to allow the health officials to take their wives away, and instead stepped forward to be sterilised themselves in an attempt to save their partners.

Very few men took part in the Quipu project, something which Lerner chalked up to a machismo society in which a man who cannot have children is seen as less of a man, and that shame and fear of losing face would have impeded them from coming forward.

As horrific as these events appear, they managed to slip under the radar for the majority of Peruvians. I asked Lerner how people thought about it at the time, and whether people were aware of the crimes being committed against the indigenous population in their country. She explained that it was a complicated situation. Many women’s rights groups supported the initiative, seeing as it was aimed to give women control over their reproductive rights, but the majority weren’t aware of how it was being carried out.

Fujimori was one of the few men present at the Fourth World Conference on Women in September 1995, and his rousing speech on women’s intrinsic place in Peruvian society would have convinced many who had doubts.

“[I created] a strategy of family planning that confronts the lack of services and information available on this matter,” he said. “Thus, women can have at their disposal with full autonomy and freedom, the tools necessary to make decisions about their own lives…These methods are available so that they can use them – I underline this – freely and responsibly, or not use them, if they opt for a different solution according to their personal or family beliefs.”

This went against the traditionally restrictive and Catholic Church-influenced beliefs that pervaded the Latin American continent, and Fujimori presented himself as a forward-thinking liberal who had women’s best interests – and autonomy – at heart.

When the initiative was first carried out, the only open critics were the Catholic Church, as well as the College of Doctors, the College of Lawyers and the Peruvian Catholic University, according to a journalistic study of Peru by Maria-Christine Zauzich. “Surprisingly few” national and international human rights groups reacted to the project, with just CLADEM and “Defensoria de Pueblo” having denounced the practice by 1998. There were people who didn’t know, and those who didn’t care, Lerner shrugged, because indigenous populations within Peru have historically held a second-class place in society.

“A lot of people here still don’t care about it because there’s still this [negative] perception,” she explained. “The situation is changing, but Peru is a very discriminatory country. It’s changing, but we still have a long way to go, and we have people who truly don’t believe that others should have the same rights.”

Giulia Tamayo gave an interview with El Periodico in 2010 when the case against Fujimori had been archived. When asked why, she agreed with Lerner that Peru was still stuck in the past.

“The power structures of the 90’s have not yet been broken down, and there are many people who were involved that are being protected,” she explained.

It is also down to a lack of knowledge, as women in indigenous societies often do have more children than urban families. This is due to the much higher infant mortality rate in these indigenous populations, as well as Amazonian tribes who have many children in order for their tribe to survive in the future. However, for those who are unaware of these factors, it is easy for them to accuse these women of “breeding like rabbits.”

“Well, it seems to me that they should be tied, because they have many children here, 6, 7, 8 and sometimes women do not want to take care of their husbands… machismo still exists, doesn’t it?” said an unnamed nurse from a health post in a rural community in Ayacucho in 2015, taken from Ainhoa Molina Serra’s paper (Forced) Sterilization in Peru: Power and narrative configurations, published by Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona.

“Because you’re getting pregnant with children like rabbits.” A woman’s testimony explaining what a nurse told her. Photo courtesy of Youtube.

This hierarchical class system in Peru is deeply ingrained into society. Indigenous populations are belittled for their poverty, disregarded due to their distance from institutions and seats of power, and are considered “ignorant,” explained Molina in her paper. “These [beliefs] are maxims that emanate from academic people, are learned and then inhabit the Lima society.”

In addition to his role in the forced sterilisations, ex-president Fujimori carried out numerous human rights violations such as murders and kidnappings during his 10-year presidency. Although in 2009 he was finally convicted to 25 years in prison due to wide-ranging human rights violations that occurred under his presidency, he was never tried for the dubious implementation of his Family Planning programme.

Fujimori was constitutionally elected three times as president of Peru, and is credited with restoring macroeconomic stability and defeating the Shining Path terrorist insurgency. He managed to gain popularity in the more remote provinces by being one of the first presidents to visit them.

“The truth is that he went there, so they saw his face, and he went with bags of rice or computers,” explained Lerner. “That’s something that in this country presidents have never done, they’ve never been there for the people so far away so in that sense he was really good.”

Mi deber era estar presente cuando el pueblo me necesitaba,anhelo fervorosamente volver a estar cerca de todos uds… pic.twitter.com/bElj7bhVE5

— Alberto Fujimori (@albertofujimori) 23 de mayo de 2015

Unlike many other Peruvian presidents, Fujimori often travelled long distances to visit remote towns and villages.

However, his presidency ended with him fleeing to Japan to escape corruption charges and he was only brought to justice five years later when he was captured during a visit to neighbouring Chile. At the end of 2017 then-president Pedro Pablo Kuczynski gave him a humanitarian pardon due to his poor health.

Corruption and impunity are a huge issue in Peruvian politics, and many saw this move as contrary to the implementation of justice. In April of this year, lawyer Luis Landa reopened the case and demanded that Fujimori be taken to court for his role within the forced sterilisation scandal.

Lerner was enthusiastic about the possible outcome of Fujimori going to trial. But would Fujimori going to prison be enough for those who are searching for justice?

“Symbolically yes,” she said. “But they need help, they need health. Some of the doctors who operated on them are still in the medical centres so they feel like they are treated even worse there than other places.

Zauzich’s 2002 journalistic study explained that the women had undergone such traumatic experiences in the health centres that they often refuse to go back.

“The health centre and health posts are considered places ‘where they hurt us,’” Zauzich wrote. “They don’t trust the obstetrician anymore, or the nurse, even if they haven’t had anything to do personally with the sterilisations…all this results in the fact that they don’t even want to go back to prevent cancer, or prenatal care…In this sense the sterilization campaigns were counterproductive and damaged the women’s trust, which will be very difficult to regain.”

The poorly-executed operations have left many of the women in constant pain, without economic resources to visit the medical centre, which may be miles away from their village, and possibly still staffed by the doctors and nurses that duped them into the procedure in the first place.

“They’re completely abandoned by their families,” explained Lerner. What often happens, Lerner said, is that their husband abandons them for their lack of ability to have children, and increased urbanisation sees their children leave to move to the countryside in an attempt to get a better quality of life.

“But they have each other,” she smiled.

One of the results of the Quipu project that Lerner is most proud of is how they managed to bring the women together. Many didn’t understand the scale of the issue, and thought that it had only happened in their town. The Quipu project encouraged them to travel to other regions, even get on a plane for the first time, in order to participate in workshops and share their experiences with others. It even incited some women to found the National Organisation of Sterilised Women in 2016, headed by Esperanza, which travels the country giving workshops and demonstrations.

“We have seen empowerment in certain women like Esperanza, who has grown to where she is now,” Lerner said. “That has been a massive success, because she has appropriated the project as her own and really grown it.”

Indigenous women protesting the shelving of the forced sterilisations case in Lima.

Photo courtesy of Youtube

The Quipu project brought the forced sterilisations of Peru under an international spotlight, rather than just a national one, which Lerner thinks may have been the key to its success.

“Because it has been so politicised, this polarity means that you’re either for it, or against it,” Lerner explained, talking of Peruvians. “That’s why I think the project has been more successful internationally. We have three audiences. The first audience was the women, the participants themselves and their communities – for them to connect with each other, and for the communities to listen to them. The second was international, and the last one was Lima and the power classes here. They are the hardest to reach, the most insensitive, but they are the ones who have the power.”

She explained that it is necessary to shame the power classes internationally in order for them to sit up and take notice, with the hope that something would get done.

“We haven’t had a single Peruvian sol for the Quipu project,” she laughed. “All our funding has come from international sources, Chile, Colombia, the US, the UK. Peru, nothing. Nobody wants to touch us.”

Despite a lack of national monetary support, the Quipu project is indebted to various Peruvian women’s organisations that helped them gain the trust and participation of the indigenous women. However, it is true that the larger women’s organisations, although recognising and strongly condemning the forced sterilisations, did not donate any money to help the creation or the publicity of the Quipu project itself.

Throughout the years following Fujimori’s presidency, there have been state and governmental-level recognitions of the forced sterilisations. In 2003, the Peruvian state recognised the crime before the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights, although there have been no judicial repercussions to this.

“Against their will” an awareness campaign for the forced sterilisations. Photo courtesy of Twitter @areccomaria1122

In response to many organisations clamouring for justice, there have also been lukewarm attempts at a governmental level to create evidence to back up the victim’s claims. At the end of 2015, a register called Reviesfo was created, where women could write their names down to affirm that they had been victims to forced sterilisations. However, two and a half years later, only 8,000 women had signed up, because the only way they could do so was to travel miles from their rural towns, which would require money, and health, that they simply didn’t have.

“It’s as if they created [Reviesfo] to get themselves out of trouble,” explained Raquel Reynoso, the coordinator for GREF, a follow-up organisation attempting to bring reparations to the women involved. “It doesn’t have the sufficient resources and it’s been given to officials who have no experience dealing with these cases.”

These responses may help in some way for the victims to feel validated, but the majority of the activities organised by groups such as GREF are protests to stop those in power forgetting about the issue, rather than helping the thousands of women who are sick, unable to work, and isolated in their rural homes. This is something that needs to be carried out at a state level in order to effectively provide a comprehensive and effective plan across the country.

Dr. Matthew Brown, a Latin American specialist at Bristol University, told Peru Reports that he hopes that projects like Quipu have opened the floodgates of evidence and that those affected will finally achieve justice.

“Fear and shame have contributed towards people taking time to come forward to give their story,” he explained. “Also persecution by the state and discouragement from family members in some cases. But there is now plenty of evidence, in Quipu and collected by NGOs and campaigners.”

However, although Fujimori’s case was opened again earlier this year, thus far there has been no follow-up on when or even if the trial will be reopened, adding to the impunity often enjoyed by politicians in the country. It may be a politicised subject that nobody wants to touch, Fujimori may be an old man with health problems, and it may mean very little to the power classes of Peru.

However, it would mean so much to these people who have been wronged by a government and have been provided with little else than scars for life, both mental and psychological.