Peru’s Congress on Monday voted to begin impeachment proceedings against President Pedro Castillo. The move comes just three months after a previous attempt by Congress to impeach him failed.

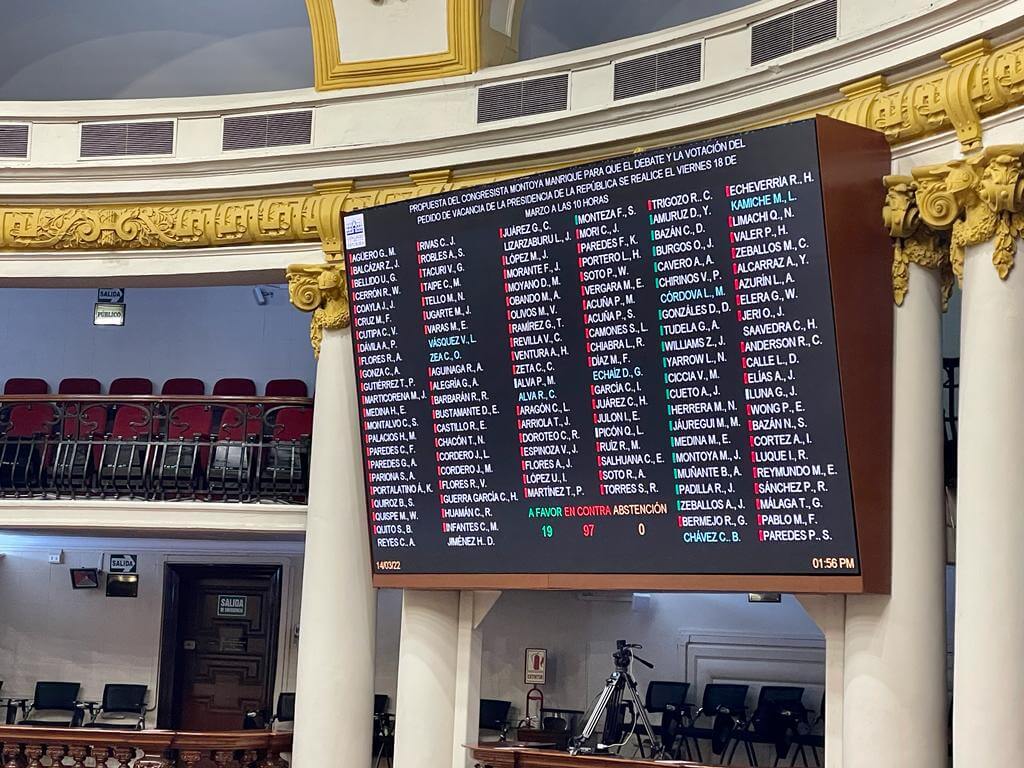

Lawmakers voted 76 to 41 to begin the impeachment debate, according to Reuters. Right-wing opponents in Congress argue that Mr. Castillo, a member of the Marxist Free Peru political party, is morally unfit for office, accusing him of numerous irregularities including corruption.

In February, lobbyist Karelim López told prosecutors that Mr. Castillo headed a “mafia” that controlled public works contracts within the Ministry of Transportation and Communications.

Congress will eventually need at least 87 of 130 total votes to remove Mr. Castillo from office following the impeachment hearing and proceedings could begin as early as this Friday.

Speaking to a crowd during an event in the Nauta indigenous community in northern Peru, Mr. Castillo responded briefly to the impeachment proceedings:

“I am sorry that the trip-ups continue and that they [Congress] are not listening to the people. Because they have just approved the [impeachment] motion with something like 54 votes … We have to tell the country that we have not come to steal a penny, and this is what we’ll tell them tomorrow in Congress,” the president said.

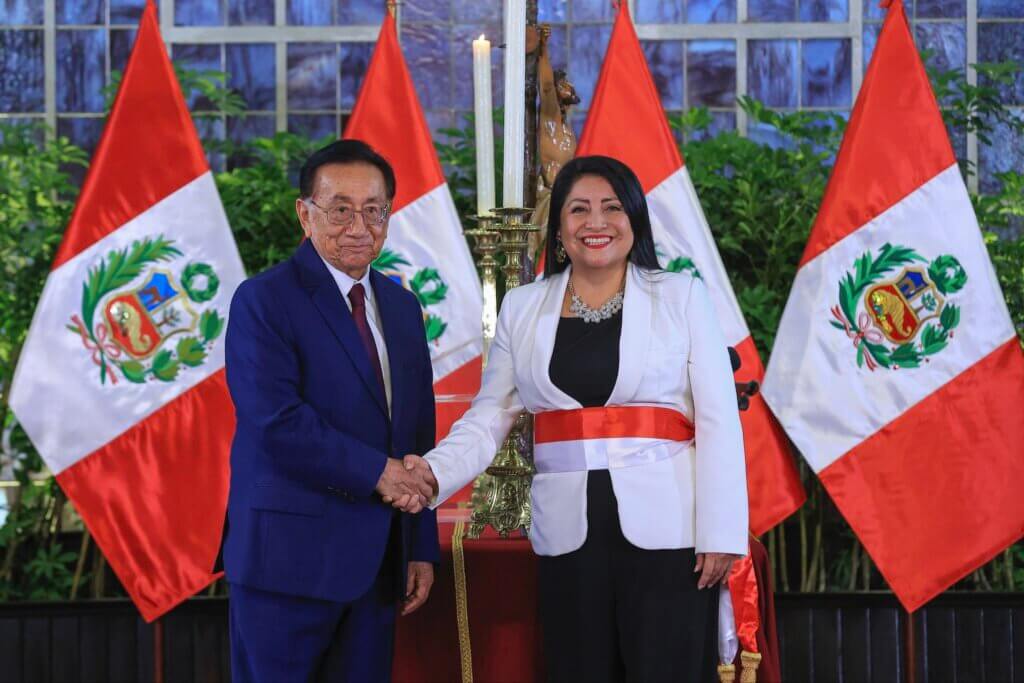

Peruvian President Pedro Castillo addressing a crowd in the Nauta indigenous community in northern Peru. Image courtesy of @presidenciaperu.

The impeachment efforts are led by right-wing opponents in Congress, including the party of Keiko Fujimori, the daughter of jailed former president Alberto Fujimori. Ms. Fujimori lost the presidential elections to Mr. Castillo in July of last year. In 2000, Peru’s Congress deemed Mr. Fujimori morally unfit for office and he was sentenced to prison in 2009 for human rights abuses and corruption.

Mr. Castillo survived impeachment in December 2021 after opponents launched an inquiry into $20,000 found in a bathroom of the presidential palace that allegedly belonged to his presidential secretary.

According to Peru’s Constitution, the presidency can be vacated for any of the following reasons:

- Death of the President.

- Acceptance of the President’s resignation by Congress.

- Leaving the national territory without permission from Congress or not returning to it within the established time period.

- Dismissal, after having been sanctioned for any of the infractions mentioned in article 117 of the Constitution.

- The President’s permanent moral or physical incapacity, declared by Congress.

Some legal experts have raised concerns in recent years about how the clause allowing Congress to dismiss a president for moral incapacity is being manipulated as a political weapon that’s destabilizing the relationship between the executive and legislative branches of government.

In January, Minister of Foreign Affairs César Landa wrote in Agenda Estado Derecho that in recent years, “the parliamentary majority has used permanent moral incapacity to oppose political and government actions or media reports, regardless of their objectivity. The vacancy, which should be linked to objective criteria, now refers to subjective criteria and political games between the Legislature and the Executive [branch] that are not healthy for the maintenance of our political system: Thus, vacancy requests are formulated based on preliminary investigations — encouraged by the media — by the parliamentary opposition that has lost the presidential elections.”

Including this most recent case, Congress has used the moral incapacity clause against presidents nine times since 1823, five of which have occurred since 2017.