Venezuelan citizens emigrating to Peru are finding a mixed back of opportunities and hospitality, but also of xenophobia and discrimination in their adopted country.

This year, the IMF predicts that inflation in Venezuela will reach 13,000 percent, as the economy is set to continue to shrink and the majority of the population is unable to afford food. It’s no wonder that more than half of young people want to leave, affirm The Guardian.

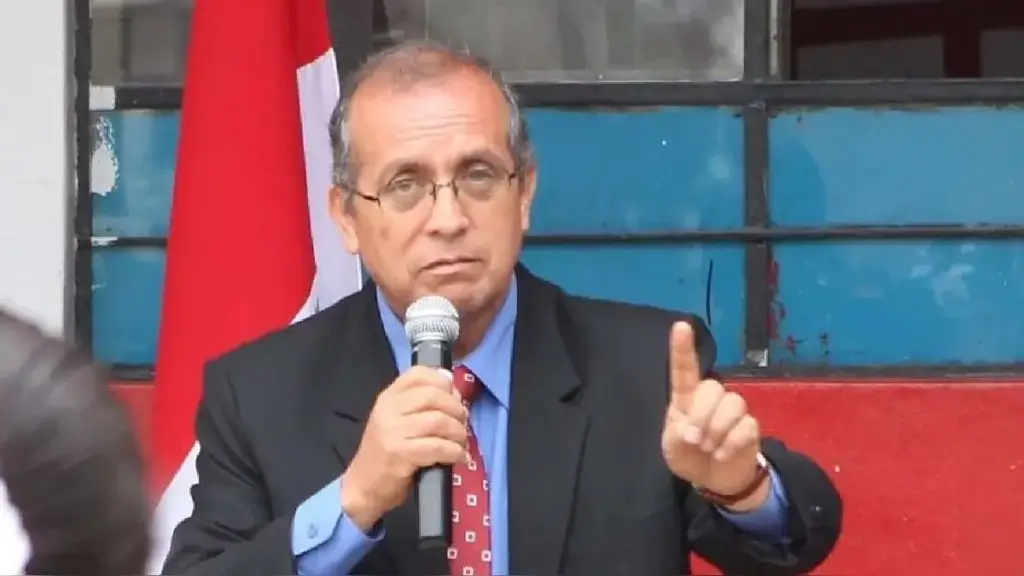

Peru President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, himself a descendant of immigrants, created the Temporary Permit of Residence (PTP) in February of 2017. This allows any Venezuelan who legally entered the country, had no criminal record and could pay the nominal fee of $13, to work, pay taxes, and have limited access to healthcare for a year. Of 26,000 people who applied, all but 500 have been accepted and are now living legally in Peru.

Kuczynski has just extended the PTP until July of 2019.

Mass immigration because of economic collapse brings with it the inevitable negative connotations of poverty and desperation. However, according to The Latin American Post, 40 percent of Peru’s immigrants hold post-graduate degrees, and are succeeding in finding employment and stability. Americas Quarterly chalks this up to Peru’s relative prosperity, with IMF predicting a 4 percent economic growth this year, and to the fact that the level of poverty has halved since 2005.

However, these stories of financial stability and economic development are not those that generally hit the headlines. Many Venezuelans arrive with nothing and are forced to work as street hawkers, selling food on the street to make enough money to survive, which has elicited some negative reactions.

Last weekend, a large poster was hung on a bridge in Lima, along with many smaller ones around the city, with the words ‘#PeruSinVenezolanos Basta Ya!,’ which translates in English to “Peru without Venezuelans, Enough!.”

This has received widespread condemnation from Peruvians on social media, with many reminding the unnamed perpetrators that “the last time we gave a Venezuelan an opportunity, we ended up calling him Liberator” in reference to Simón Bolívar, who freed Peru from Spanish Colonialism in the 1820s. However, the posters are proof that negative feelings towards Venezuelans do exist.

In a response to the growing negativity around Venezuelan immigration to Peru that increased at the beginning of this year, a group of Venezuelans who are living in Peru made a Youtube video called No a la Xenofobia (No to Xenophobia), denouncing stereotypes and encouraging inclusivity.

Quotes such as “I’m Venezuelan, I live in Peru, and I have never used my body as a tool to reach my work goals,” show the unfair stereotypes that have been placed on the community. Rather than combating negativity in kind, the video has a hopeful outlook, highlighting the productive immigration between both countries over the years.

Television channel CNA, part of Peru’s ATV network, also highlighted the discrimination towards Venezuelans. They carried out a social experiment showing the sexual harassment that female Venezuelan street sellers have to deal with on a regular basis. Now on Youtube, the clip included below shows Carmen Herrera, a qualified lawyer who had to leave Venezuela because of the crisis. She said she now sells tizanas (a typical Venezuelan drink) on the streets of Lima, and told the CNA of the comments she gets from men.

“I’ll buy all of your drinks if you come in the car with me”

“Why are you so pretty?”

She says they try and grab her hand when she takes the money, and this harassment happens every day. The television channel dealt with the topic in a serious manner, and urged watchers to have “more respect.”

In San Juan de Lurigancho, an area of Lima, René Cobeña, a textiles businessman opened a free hostel for Venezuelans. The guests work together to complete daily chores, to ensure everyone has a meal for the day, and also make arepas, bombas and tizanas to sell on the streets.

However, it is now in crisis, as the hostel was meant for 20 people, but now hosts at least 90. René told América Noticias that he couldn’t turn people away, because they often turned up with children. They sleep on the floor on inflatable mattresses, but they’re running out of space.

“If it keeps filling up, people will have to sleep outside,” Cobeña told El Comercio. “We need help for these families. Any free space, a garage, a flat or a terrace is useful to help. I’ve had to stop paying for my daughter to go to university to carry on renting this place, but the compensation is seeing these people able to create a new life”

If you are in Lima and can be of any assistance, call (+51) 944973060.