From an anti-corruption activist to a fugitive from justice, a look at the tragic trajectory of Peru’s former President Alejandro Toledo.

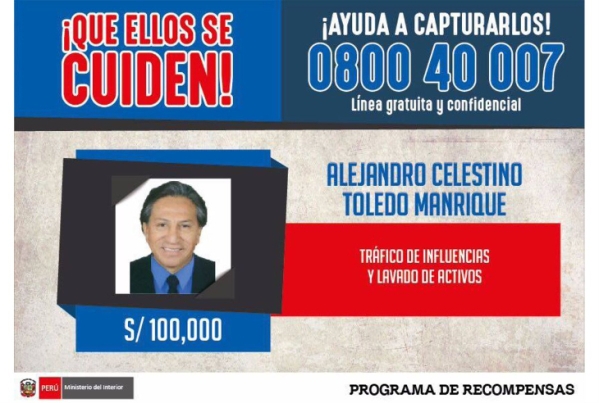

A judge in Lima on Thursday ordered Toledo jailed for 18 months while he faces trial, a common practice for defendants who pose a flight risk, for money laundering and influence peddling. Toledo is accused of taking $20 million in bribes from Brazilian construction firm, Odebrecht. Peru has issued an international arrest warrant and is offering a $30,000 reward for information leading to Toledo’s capture.

“I am not running. I will face these baseless accusations,” Toledo tweeted last year in one of many proclamations that he would face justice in Peru.

Now that he has been charged, however, the man who rose from a life of poverty in Ancash to study at Stanford, work for the World Bank and ultimately be elected president of Peru has gone into hiding to avoid arrest. Israel, where Toledo’s wife holds citizenship, has barred Toledo’s entry. Officials believe he is in the United States after visiting France.

“I’ve never run from anything, but they call me a ‘fugitive’ – a Machiavellian political distortion that I reject,” Toledo tweeted from hiding yesterday. He also posted a letter arguing that he was the victim of a “politically motivated” lack of due process.

Toledo’s disgraceful situation marks the beginning of the end of what was once an inspiring Cinderella story. Born into a large Quechua family in Ancash, Toledo grew up with no electricity or running water. He impressed two Peace Corps volunteers on vacation in Chimbote, who paid for him to study in the United States. He ultimately earned postgraduate degrees from Stanford University.

Toledo worked at the World Bank, Inter-American Development Bank and United Nations before entering politics in Peru. In 2000, Toledo ran for president promising “The second chapter of Fujimorism” against then-President Alberto Fujimori. Toledo lost the contested election and led large protests in downtown Lima calling for Fujimori to resign.

Fujimori’s regime fell after the publication of videos showing his spy chief, Vladimiro Montesinos, bribing politicians and business leaders. Toledo positioned himself as an anti-corruption candidate to win special elections in 2001, becoming South America’s first democratically elected President of indigenous descent.

Peru’s economy continued to improve during Toledo’s government. Most notably, Toledo orchestrated the conditions for foreign energy companies to develop the natural gas fields at Camisea. The massive reserves had been discovered in 1984, but global energy firms balked at developing them in the face of successive governments’ refusal to allow the gas to be exported.

Production at Camisea has since paid over $8 billion in taxes to Peru’s government and accounts for 0.8% of GDP growth each year.

Toledo also signed a key trade deal with the United States and helped diversify Peru’s export portfolio. Inflation continued to decline as Toledo implemented more privatizations in following the market-reform policies of Fujimori.

While Toledo’s economic performance was regarded as positive, his approval ratings sunk to single digits due to high-profile corruption scandals involving people in his administration, labor strikes and even his refusal to recognize a lovechild.

After his presidential term, Toledo returned to the United States to work in academia and public policy. He worked for Stanford, the United Nations and Brookings Institution.

In 2011, Toledo returned to Peru to run for a second term as president. He enjoyed frontrunner status in the late months just before the election, but his support plummeted after he voiced support for abortion, gay marriage and legalizing drugs in this deeply conservative and Catholic society.

Those comments came just as Correo published receipts from Toledo’s government showing hundreds of thousands of dollars spent on alcohol. The receipts account for 1,753 bottles of Johnny Walker – almost a bottle per day – in addition to wine and other liquors.

Toledo ultimately won just 15% of the vote, placing fourth behind eventual winner Ollanta Humala, Keiko Fujimori and current President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski. But his political future was rendered unviable with his new image as an alcoholic.

Toledo became the butt of a joke and subject of internet memes as a hard partying drunk. Pictures of him in dance clubs and with women often went viral. A few awkward and sometimes bizarre appearances on television or radio cemented the image.

In 2013, Peruvian investigators discovered Toledo’s connection to Costa Rica-registered consulting firm Ecoteva, which they suspected was a shell used to launder and repatriate illicit money to Peru. Toledo’s image morphed from being an alcoholic to a corrupt alcoholic.

Toledo made his situation worse with inconsistent explanations of how he purchased real estate in Lima’s swankiest neighborhoods. In statements to investigators, he said he purchased a $3.8 million home in part with Holocaust reparations paid to his mother-in-law, Eva Fernenburg. El Comercio reports at least six times Toledo contradicted previous statements in regards to the purchase of the home.

Despite his image as a drunk and the suspicion of corruption, Toledo mounted an ill-advised campaign for president in 2016 elections.

“He has no chance in the 2016 elections,” Carlos Bruce, a former Cabinet minister in Toledo’s government, told RPP at the time. “And about convening a [protest march] because his [corruption] case is being delayed, I would suggest as a dear friend that he not do it because nobody is going to follow him. Nobody will get behind him.”

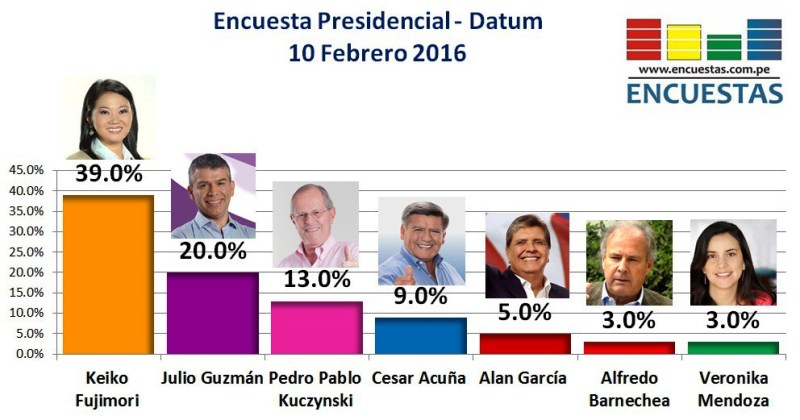

Toledo peaked in the polls at fourth place with 7% of voter intentions a full year before the first round of voting, before most competitive candidates announced their candidacies. He gradually fell to eighth place with just 2% support by January 2016.

And despite two leading candidates being removed from the ballot for electoral violations, Toledo still placed eighth with just 1.3% of the vote. His party, Possible Peru, performed so badly that it lost its legal inscription for not meeting the 5% elections threshold. Carmen Omonte, one of the party’s most visible politicians, publicly faulted Toledo before resigning from the party weeks later.

By refusing to withdraw from the ballot as leaders from the Peruvian Nationalist Party and National Solidarity did to avoid losing their inscription, Toledo has effectively run Possible Peru into the ground. The party must now obtain 500,000 signatures as its founder, on the run and facing jail, to earn its inscription.

“The moral damage is immeasurable because Toledo was the first president elected after the fall of the corrupt regime of Alberto Fujimori and Vladimiro Montesinos … and was chosen to be a morally exemplary leader, not only to recover public confidence in the democratic system, but because his humble beginnings and life story served as a model to follow for many Peruvians,” Ipsos pollster Alfredo Torres writes in El Comercio.

“Disappointment (24%), indignation (22%), treachery (16%) and anger (8%) are some of the feelings aroused by the steady reports of corruption against somebody who was once the symbol of Peru’s indigenous. The inevitable consequence is an increase in a public lack of trust. Today 87% of the population thinks that all or most politicians are corrupt and 60% think all or most Peruvians are corrupt.”

Sources

Vino, venció y coimeó: un perfil de Alejandro Toledo (El Comercio)

Toledo hizo polémicas declaraciones sobre consumo de drogas y aborto (El Comercio)

Juez ordenó 18 meses de prisión preventiva para Toledo (El Comercio)

Lo bueno y lo malo del primer gobierno de Alejandro Toledo (El Comercio)

PUNTO POR PUNTO: las contradicciones de Alejandro Toledo en el Caso Ecoteva (El Comercio)

Parejas maléficas, por Alfredo Torres (El Comercio)

Facturas que confirman gastos excesivos de Toledo en licores (Correo)

Peru Elections: Toledo the epicurean (Living in Peru)

Second former Peru president faces inquiry before campaign (Reuters)

Elecciones Perú 2011: Análisis de campañas (El Comercio)