Peru’s Congress has passed a bill that would extend the terms of liquidation for bankrupt companies in an effort o save the La Oroya smelter in Junin.

The legislative session began with a debate between two different bills which looked to reopen the 96-year-old smelter in one of the world’s most polluted cities, La Oroya. Some legislators criticized the principle of passing a law designed solely for Doe Run, the company which owns the La Oroya smelter and La Cobriza copper mine.

A bill forwarded by President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski’s government would have allowed creditors to extend those proceedings by two years. A competing proposal by the Popular Force party would require the president to issue a supreme decree to extend liquidation proceedings by one year in situations which need to respect workers’ rights and environmental standards.

Both bills were widely criticized by Peru’s media. The government’s bill was criticized for giving two more years to a company which had proven unable to find a solution for a year and a half, since the previous government extended the six-month liquidation proceeding by one year in the midst of last year’s mineworker protests which left one dead.

The Popular Force bill was criticized as a statist solution for its removing the decision to extend liquidation proceedings from the company’s creditors to the federal government.

Congress ultimately merged the two proposals into one bill which incorporated elements of both policies. The law allows creditor boards of companies to extend liquidation proceedings by one year, after which the president can issue a supreme decree to extend proceedings for another year in order to meet “obligations to respect existing law, with an emphasis on environmental and labor standards.”

The hybrid bill passed unanimously with 108 votes for and five abstentions. The change to Peru’s bankruptcy law was hailed by officials from Kuczynski’s government and the Popular Force party which controls Congress as a measure that will save 1,400 jobs at the historic smelter in rural Junin.

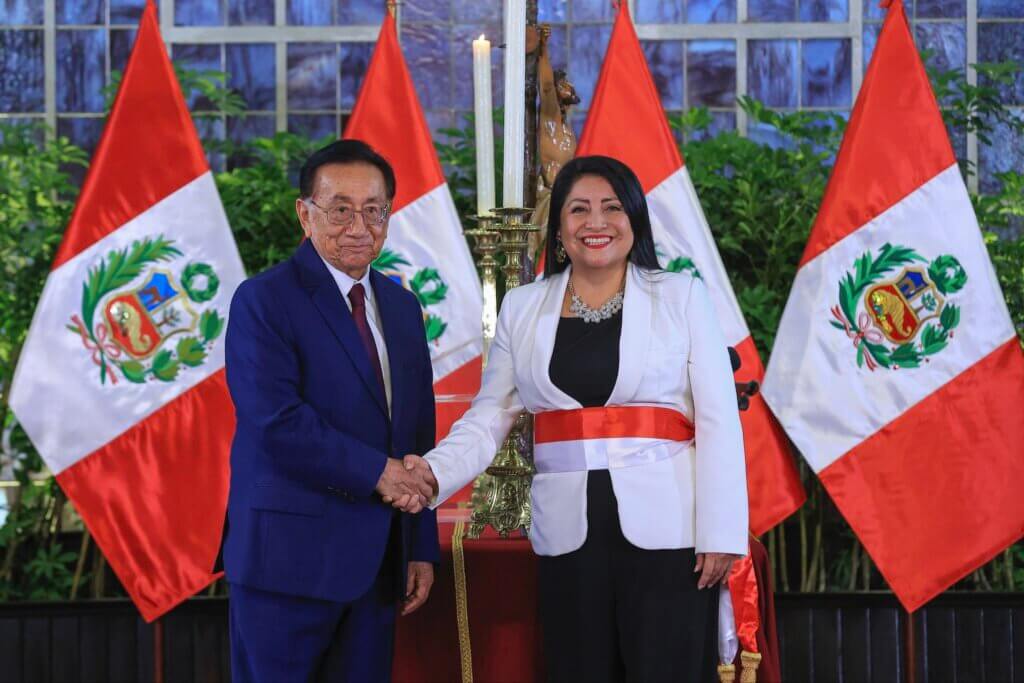

“This way, we found a solution that covers not just one company but for a group of large companies that may face a situation of being in dissolution and liquidation,” Peruvians for Change congresswoman Mercedes Araoz said in response to critics who point out that Doe Run is Peru’s only company in liquidation proceedings.

“These proposals [could have] with their own name and last name of Doe Run, which is the owner of what was previously Centromin Peru,” Popular Action congressman Victor Garcia said. Four of the abstentions came from the center-left Popular Action party, while one came from left-wing Broad Front congresswoman Maria Foronda.

Peru’s government is Doe Run’s largest creditor due to hundreds of millions of dollars in environmental fines, and thus controls the company’s board of creditors. Assuming the board requests a one-year extension, the company will enter a third year of liquidation proceedings in an economic situation which critics call untenable.

The company’s liquidation proceedings have failed to find an investor because of liabilities exceeding $500 million, environmental regulation which would require significant investment in upgrading the smelter and low commodity prices.

At the same time, allowing the smelter to fold is politically difficult given it supports 1,600 jobs. Without those jobs the city of La Oroya, with a population of 24,000, would likely become a ghost town. Both the Peruvians for Change and Popular Force parties promised local residents that they would work to keep La Oroya operational during 2016 elections.

Environmentalists would argue that La Oroya should be abandoned given its appalling health conditions. The city achieved infamy when TIME magazine named it one of the world’s ten most-polluted cities. A 2005 study showed that over 97% of children unacceptable levels of lead in their blood.

Keeping La Oroya open would require significant sacrifice in environmental standards. Labor leaders are calling for an easing of the emissions standards to make the smelter more attractive to investors. Advocates say that much of the environmental damage was done before Doe Run took over in 1997. But forgiving Doe Run’s environmental fines may also be required to bring a new company to the table.

This is the dilemma Kuczynski’s government must navigate now that they have more time to find an investor. In justifying the change to the bankruptcy law, Kuczynski argued that the previous government of Ollanta Humala left the situation untenable when it extended liquidation proceedings last year without pursuing change. Humala’s government rejected relaxing environmental standards for La Oroya.

“Last year, or up until that year, there was no clarity in policy because there was no policy from the previous government in this case. They left us a hot potato and we’ll call it as it is,” Araoz told reporters. “Today, through this move with Congress we are giving a little relief and may now the liquidation board may find investors interested in this process.”

The La Oroya smelter has not produced metals for years, but workers’ salaries are financed by copper production at the La Cobriza mine.

Yauli province mayor Carlos Arredondo told RPP that the smelter’s lead and zinc circuits would comply with emissions standards, and that the copper circuit is the only one out of compliance.

Sources

Congreso aprobó proyecto que amplía plazo de liquidación de procesos concursales (Andina)

Aráoz: Anterior gobierno nos dejó La Oroya como papa caliente (El Comercio)

Una nueva prórroga para Doe Run [INFORME] (El Comercio)

Doe Run: Congreso amplió solo por un año plazo de liquidación (Gestion)